In the heart of China’s rich cultural heritage lies an exquisite craft that has captivated artisans and collectors for centuries: the delicate art of filigree and soldering, known locally as huasi handian . This intricate technique, which combines fine metal threads with precise soldering, has been passed down through generations, embodying the pinnacle of Chinese jewelry and metalwork craftsmanship. The tradition is not merely a technical skill but a testament to the patience, precision, and artistic vision of its practitioners.

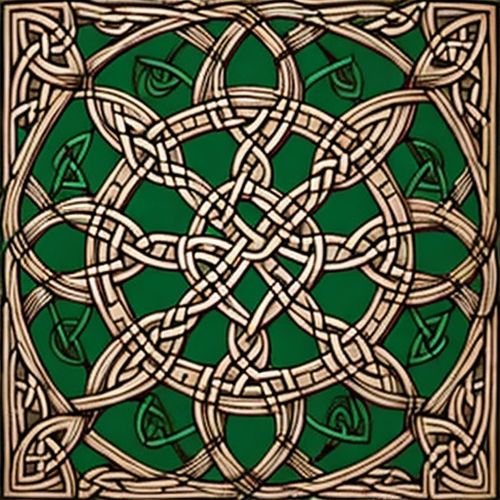

The origins of Chinese filigree can be traced back to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), where it flourished alongside other metallurgical advancements. By the Tang (618–907) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties, the craft had reached unprecedented levels of sophistication, often adorning the imperial court’s jewelry, hairpins, and ceremonial objects. The term huasi (花丝) refers to the painstaking process of twisting and weaving fine strands of gold or silver into floral and geometric patterns, while handian denotes the nearly invisible solder points that bind these threads together without compromising their delicate beauty.

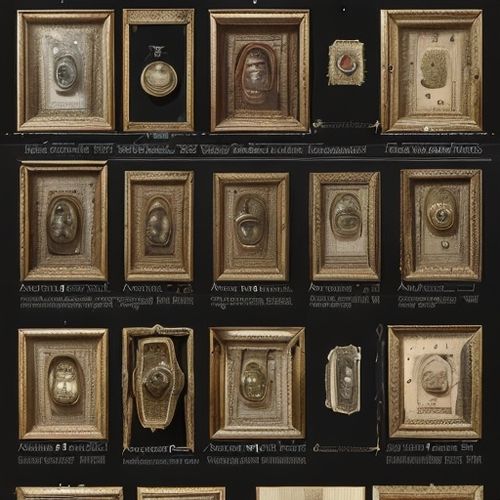

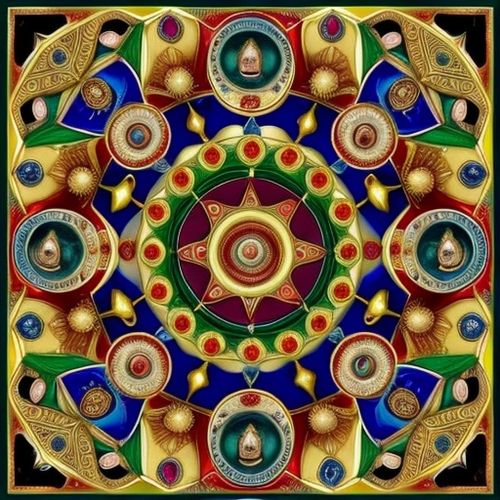

What sets Chinese filigree apart from other metalworking traditions is its emphasis on minute detail and structural harmony. Artisans often work with threads as thin as a human hair, shaping them into intricate designs that mimic nature—lotus blossoms, peonies, and mythical creatures like dragons and phoenixes. The soldering process is equally demanding; a single misstep can ruin hours of labor. Masters of the craft employ a blend of traditional tools and modern techniques, using borax as a flux to ensure seamless joins that are both strong and invisible to the naked eye.

Despite its historical prestige, the art of huasi handian faces challenges in the modern era. The rise of mass-produced jewelry and declining interest among younger generations threaten its survival. However, efforts are underway to preserve this intangible cultural heritage. Workshops in Beijing and Chengdu, often led by National Living Treasures—artisans recognized by the Chinese government for their mastery—are reviving the craft through apprenticeships and exhibitions. Museums, too, are playing a role by showcasing antique filigree pieces, reminding the public of their cultural and artistic value.

For collectors and connoisseurs, Chinese filigree represents more than just an art form; it is a bridge between past and present. Contemporary designers are experimenting with huasi handian, blending traditional motifs with modern aesthetics to create pieces that appeal to global audiences. Auction houses have noted a surge in demand for antique filigree works, with some pieces fetching astronomical prices. Yet, beyond its market value, the craft endures as a symbol of China’s enduring dedication to beauty, precision, and cultural continuity.

The future of huasi handian may hinge on its ability to adapt. Some artisans are exploring collaborations with fashion houses, while others integrate the technique into wearable technology, proving its relevance in an ever-changing world. What remains unchanged, however, is the reverence for the human hand’s ability to transform metal into poetry—one thread, one solder point at a time.