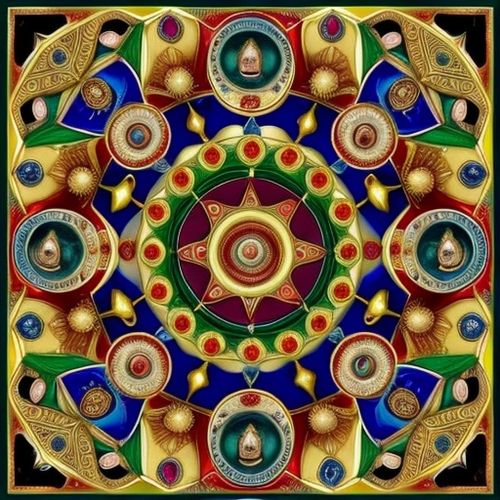

The discovery of the Maya jade mask has sent ripples through the archaeological community, offering a rare glimpse into the sophisticated artistry and spiritual depth of one of history's most enigmatic civilizations. Unearthed from the depths of a sacred tomb in the ancient city of Palenque, this intricately carved artifact is more than just a relic—it’s a portal to understanding the Maya's reverence for jade, their cosmological beliefs, and their unparalleled craftsmanship. The mask, dating back to the 7th century, is believed to have adorned the face of a revered ruler or high priest, serving as both a symbol of divine authority and a conduit to the afterlife.

The significance of jade in Maya culture cannot be overstated. Unlike other Mesoamerican civilizations that prized gold, the Maya held jade in the highest esteem, associating it with immortality, power, and the life-giving forces of water and vegetation. The vivid green hue of the stone was thought to embody the essence of the natural world, making it a sacred material for rituals and royal regalia. The mask’s craftsmanship—meticulously polished and inlaid with obsidian and shell—reveals a level of technical skill that rivals modern lapidary work. Each curve and contour was designed to reflect the wearer’s status and connection to the gods, with symbols of the Maize God and the Jaguar Spirit woven into its design.

What sets this mask apart from other Maya artifacts is its near-perfect preservation. While many jade objects have been found fragmented or eroded by time, this mask was shielded by the sealed chamber of its tomb, its colors still vibrant after over a millennium. Archaeologists were stunned to find traces of cinnabar—a mercury-based pigment—lining the mask’s edges, suggesting it was part of a ceremonial paint ritual. This discovery has reignited debates about the Maya’s use of toxic materials in spiritual practices, hinting at a complex interplay between beauty, danger, and the divine.

The mask’s discovery also sheds light on the political and spiritual landscape of Palenque during its peak. Historical records point to the reign of King Pakal the Great, whose tomb in the Temple of the Inscriptions remains one of the most elaborate Maya burial sites ever found. Some scholars speculate that the mask may belong to a lesser-known successor or a high-ranking shaman, given its stylistic deviations from Pakal’s iconography. Either way, its presence underscores Palenque’s role as a hub of artistic innovation and theological discourse, where jade was not just adornment but a language of power.

Beyond its historical value, the mask raises poignant questions about cultural patrimony. As Guatemala and Mexico vie for ownership of the artifact—both claiming ties to its provenance—the mask has become a flashpoint in the broader conversation about repatriating looted antiquities. Meanwhile, indigenous Maya communities have voiced their desire to reclaim not just the object but its spiritual meaning, urging museums to treat it as a living relic rather than a static exhibit. This tension between preservation and reverence continues to challenge the ethical frameworks of modern archaeology.

Technological advancements have allowed researchers to probe the mask’s secrets without damaging it. CT scans revealed hidden inscriptions beneath the jade panels, likely prayers or invocations meant to guide the wearer’s soul. Spectrographic analysis confirmed the jade’s origin as the Motagua River Valley in Guatemala, a region famed for its high-quality stone. These findings are rewriting assumptions about Maya trade networks, proving that even in a world without wheels or beasts of burden, their commerce spanned thousands of miles.

The mask’s legacy endures not just in museums but in contemporary Maya culture. Modern artisans in Chiapas and the Yucatán still carve jade using traditional techniques, passing down stories of how their ancestors believed the stone held the breath of the gods. For them, the rediscovery of this mask isn’t just an academic triumph—it’s a reclamation of identity. As exhibitions tour globally, the mask serves as a reminder that the Maya civilization, though often relegated to history books, is very much alive in the hands and hearts of its descendants.